There’s still a long way to go before we achieve true diversity in tech

Yay — this week is International Women’s Day.

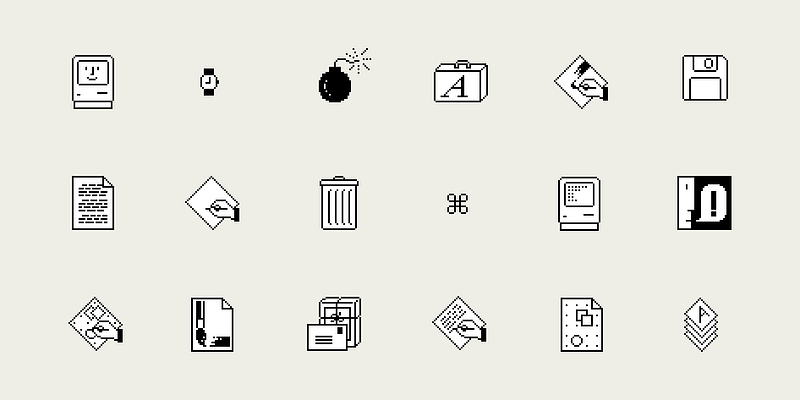

In honour of some auspicious and very creative and clever women in computing and engineering, we’ve written a post on our website about some wonderful women who have made an incredible impact on technology including the woman that gave the Apple Mac interface its friendly design feel (before the era of Jonathan Ive) Susan Kare, and Margaret Hamilton.

While there are some incredible women who have made great contributions to the world of tech, we still have a long way to go before the industry balances out in terms of gender.

There is still a dearth of women both studying computer science and working as software engineers. Only 11% of students studying computer science at A-level are female and with such a small percentage of women studying computing, it follows that there is a large gender imbalance when it comes to the tech workforce. Apple is one of the best performers when it comes to diversity and as of 2017, only 23% of tech roles at the company were filled by women.

Not only are young women missing out on some of the highest paid jobs upon graduating from university (earlier this year The Times published a piece showing that Computing grads earn an AVERAGE of £50K upon graduation as a starting salary); BUT this means that roughly half the population — women — are using products built predominantly by men.

The average starting salary of a computer science graduate is £50K per annum.

So… the algorithms that decide what music Alexa plays for me or the ads that appear when I’m reading the news, those decisions have all been written into software by programmers that are disproportionately male.

Unfortunately, the gender imbalance can result in products that reflect a similarly unbalanced view of the world. Caroline Criado-Perez’s new book, Invisible Women, points out that only 3.3% of protagonists in video games are female, for example. The playing and modding of video games is one of the most popular routes into computer programming. These sorts of disparities are a real turn off for girls who might otherwise want to explore this route into programming.

While the playing and modding of video games is one of the most popular routes into programming, only 3.3% of protagonists in video games are female.

We need to balance out the pipeline to get more women into the industry

If we’re to balance out gender amongst tech workers, we first need to balance out the pipeline. The pipeline is the number of graduates entering into the field and if few girls are studying computing, it follows that there will be few female software engineers. ( ‘Technically Wrong’ by Sara Wachter-Boettcher discusses gender disparity in the pipeline at length and biases written into the tech products we use).

The problem, however, is not insurmountable. Through educating girls about what is achievable with code and making it relevant, we can certainly increase the number of girls studying computing.

Baby steps…

Big issues like industry-wide gender disparity take time to resolve; the good news is there are achievable steps we can take to inspire more girls to get coding.

Focus on the creative product, not the jargon.

Research suggests that girls are much more responsive to class descriptions that focus on creativity and specificity (eg. ‘Remix music with code’). Coder Dojo Scotland has done a wonderful study on factors that encourage an increase in female participation on coding clubs.

If you ask girls if they’d like to design a better Instagram or Snapchat, that will feel much more relevant and exciting than asking them if they’d like to learn Python.

Combat gender stereotypes.

Because coding clubs can be very dominated by boys, it can become intimidating for girls to join when they’re very much in the minority. It’s important to get girls interested in coding from a young age and ensure they stick with it so that they don’t get pushed out or assume it’s ‘not for them’ as they get older.

Educate girls as to the creative possibilities of tech.

I remember proposing a coding club to a girls school in West London and was quickly dismissed with ‘we’ve tried a coding club in the past but there wasn’t enough interest.’ It was incredibly frustrating to see their students written off like this.

Sometimes girls hear coding and think of lines of dreary code or boring exercises, but show them something creative and visual and their interest might be piqued. Getting girls interested in coding might be a matter of educating girls as to how creative and rewarding coding can be.

For more about blueshift and our creativity-led approach to coding, check out our courses.